At first glance, the makeup kit looks like any other. Half open, it’s covered in the type of grime that only accumulates with heavy use — a sort of shimmery muddle of powders, foundation and small flashes of glitter.

One unusual item: a small card depicting a figure hard to make out under layers of makeup.

“That’s a St. Michael, the archangel, holy card,” says Ian Darnell, Missouri History Museum assistant curator of LGBTQIA+ collections. “Michael because of Michael Shreves [who] used that for contouring, so it’s encrusted in makeup.”

Shreves is perhaps best known as Michelle McCausland, a celebrated St. Louis drag queen who was a plaintiff in a 1986 ACLU lawsuit that overturned the city’s ordinance banning masquerading — or wearing clothing of the opposite gender.

The card and the makeup kit are part of the history museum’s new exhibit Gateway to Pride, which launches tomorrow and will be open through Sunday, July 6, 2025. It’s the museum’s first-ever exhibition dedicated to tracing the history and contributions of LGBTQ+ St. Louisans.

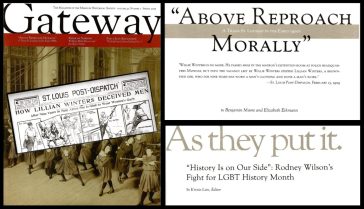

In Gateway to Pride, the Missouri History Museum will present the first-ever full-scale exhibit on St. Louis’s fascinating and powerfully relevant LGBTQIA+ history. (Courtesy Missouri History Museum)

It’s a history that was overlooked for far too long.

“You can’t understand St. Louis in the past or in the present without taking into account the struggles and achievements of the LGBTQIA+ people who’ve made lives for themselves here,” Darnell says. “This exhibit is an extraordinary opportunity to let members of the community see St. Louis’ past from a fresh perspective, to see just how integral LGBTQ+ people have always been to the history of this place.”

Jody Sowell, president and CEO of the Missouri Historical Society, adds that he hopes the exhibit will be a model for museums across the country.

“[It will be a model for] how to tell more inclusive history and how to tell that history in ways that are relevant and resonant and memorable,” he says. “So I’m excited for St. Louisans and everyone who comes to the history museum to come see this.”

Much of the exhibit draws from artifacts collected through the St. Louis LGBT History Project and the Gateway to Pride initiative, a community project to preserve the artifacts, oral histories, photographs and more of queer St. Louisans. Gateway to Pride highlights “some of the best” of what the project has collected.

The exhibit is broken into five sections that begin in the 18th century and end in the present day. Visitors walking in are greeted by an intro video made up of some of the oral histories, which includes St. Louis-native Andy Cohen’s story. The same section introduces essential concepts of gender and sexuality.

One interesting inclusion is a prophylactic label from the 1940s that the museum found tucked into the cap of a WWII naval uniform that had been donated.

“It’s just a way of getting into the idea that sexuality is always there [in] the human experience,” Darnell says.

The first chronological section after the intro looks at the origins of St. Louis’ LGBTQ+ communities in the 19th and 20th centuries and includes a profile of Harriet Hosmer, who is considered the first female professional sculptor. She had come to St. Louis to study anatomy at the St. Louis Medical College and formed a

Missouri History Museum staff members install Greg Gerhart’s ACT UP coffin. (Courtesy Missouri Historical Society)

lifelong connection to the region that included sculpting the statue of Thomas Hart Benton that still resides in Lafayette Park.

Darnell explains that the exhibit doesn’t refer to her as a lesbian because the term would be anachronistic but that she had a series of intimate relationships with women, which included a partner of 25 years — a Scottish noblewoman who served as a patron also.

The exhibit also includes a first-edition copy of Claude Heartland’s The Story of a Life, which was published in 1901, and is the first known autobiography of gay life in St. Louis. There’s also a section on the bans on cross dressing that includes the stories of Florence Smith, a Black trans woman who was repeatedly arrested for masquerading, and John Berger “who was arrested wearing a natty brown suit and a brown hideaway coat.”

Things move into the 1950s through the 1990s and the way public community and LGBTQ+ rights emerged. The exhibit also includes a section on nightlife and includes a mirrorball from the now-closed Central West End bar Magnolia’s and gowns worn by local drag queens and a binder from a drag king.

“For many queer people in St. Louis over the years, it was an essential space,” Darnell says. “For a lot of people, nightlife is one of the only spaces where they can look and feel like they love themselves.”

One of the most affecting objects in the exhibit is the ACT UP coffin created by Greg Gerhart after his friend Dennis Chambers died of AIDS-related complications. Within the coffin are Chambers’ hospital bands, and he would bring the coffin to demonstrations as a sort of “container for a holy object and a memorial to everyone who was lost because of the AIDS crisis,” Darnell explains.

The final section goes to the present day and includes the fight for marriage equality, the concept of family, transgender activism, the ballroom scene and so much more. Then visitors will find themselves back at the start of Gateway to Pride — a purposeful choice.

“In order to leave you have to go back through the intro section, through these voices in the oral history of the big picture of it all [and understand] why it’s important to save this history,” Darnell says. “…[It] will make sense in a different way.”