University of Kansas women’s, gender, and sexuality studies professor Katie Batza claimed some of the terrain of research into LGBTQ healthcare infrastructures and socio-medical responses to LGBTQ patients with her 2018 book Before AIDS: Gay Health Politics in the 1970s, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press. She’s annexed more of the territory of health care and medicine in the lives of LGBTQ Americans in her new book from the University of North Carolina Press, AIDS in the Heartland: How Unlikely Coalitions Created a Blueprint for LGBTQ Politics.

AIDS in the Heartland is an academic exploration of the imagined and real heartlands of the United States – the “white heartland imaginary,” Batza names it, where whiteness, bootstrap-orientation, respectability, family, home, and faith are imagined as the supreme virtues of a space and an idea. Batza’s book is about how this geographic terrain was affected by the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, in ways reflective of and divergent from coastal cities like New York and San Francisco, and how the 1980s and 1990s accommodations to this demanding heartland ideal continue to inform LGBTQ advocacy and politics to this day.

The first and last thirds of this book wrestle with the precise ways in which white heartland imaginary concepts of respectability and assimilation (not rocking the boat) demanded a Midwest approach to power dynamics during the first two decades of the AIDS years. The penultimate chapter ties the thread together and reveals how this temporal-geographic response became a template for national LGBTQ rights work in the battles for LGBTQ equality in the military and in marriage, both respectable “white heartland imaginary” institutions.

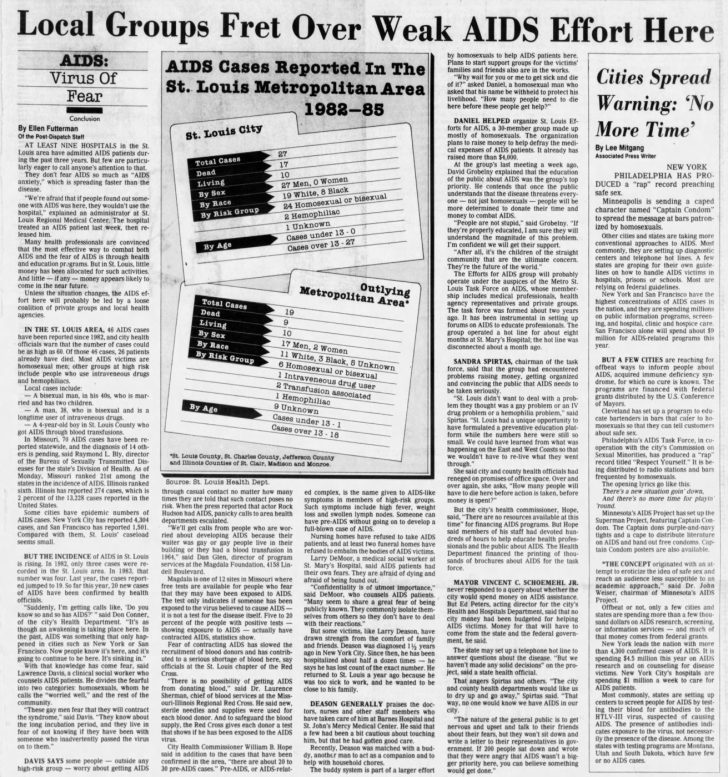

Batza also compares heartland motivations and actions to the east and west coasts’ philosophical grounding and subsequent AIDS response. One contrast between the eastern seaboard and California and the hinterland, according to Batza, is heightened interior religiosity: “The heartland response to the early AIDS crisis was infused with religion at every turn.” Batza’s book chronicles the religious good – Trinity Episcopal Church in St. Louis; the trying-to-be religious good (and doing good works) – DOORWAYS of St. Louis; and the religious bad – the Westboro Baptist Church of Topeka, Kansas. How each of these institutions navigated rising AIDS waters is chronicled here.

The Central West End’s Trinity Episcopal Church, for example, was a beacon of liberal-inclusive Christianity in St. Louis long before the AIDS pandemic. At various times, it provided meeting space for the Mandrake Society, the first homophile organization in St. Louis, founded two months before Stonewall; for Integrity (a gay Episcopal group); for Youth of America (a gay youth group); for St. Louis Effort for AIDS (founded in 1984); for PREP / PROMO (statewide LGBTQ rights advocacy group founded in 1986); and for a short-lived ACT UP chapter of St. Louis. Trinity also offered in-home same-sex blessings in the early 1960s.

Alongside St. Louis’s Trinity, the Rev. Michael Allen, Dean of Christ Church Cathedral, regularly engaged the St.Louis news media on behalf of people living with AIDS, once famously announcing that “Christ Church has AIDS.” Rabbi Ruben, Temple Israel, served on an interdenominational working group for DOORWAYS, which provided needed housing for people living with AIDS. Even the St. Louis Archbishop John L. May tried to move the official Catholic conversation toward a more centrist place in response to AIDS, eventually losing the debate to New York’s Cardinal O’Connor, against whom ACT UP New York often demonstrated.

Batza also introduces readers to many heartlanders who stood up to address human suffering during the AIDS crisis. Dr. Donna Sweet of Wichita, Kansas, for example, is a straight-white-woman who grew up on a farm in a conservative family who became, according to Batza, as “a literal one-woman regional AIDS response” in Kansas. As gay men living with AIDS returned to their homes of origin, Dr. Sweet was “the AIDS doctor” who provided care for them and for hundreds of other Kansas AIDS patients. She eventually earned certification from the American Academy of HIV Medicine Specialists and at one time had five AIDS clinics across Kansas, serving as the primary AIDS specialist for thousands of patients with AIDS. To this day, “she remains…the only AIDS specialist in the state and currently has a caseload of well over 2,000, including every HIV-positive Kansan.”

Minnesotan Carole laFavor, a “butch lesbian two-spirited nurse” and Ojibwe nation member, was diagnosed with HIV in 1986. She became “a leading activist” for Native Americans with HIV/AIDS. “Obviously,” she is quoted in a mass mailing from the CDC as part of their American Responds to AIDS Campaign, “women can get AIDS. I’m here to witness to that. AIDS is not a ‘we,’ ‘they’ disease, it’s an ‘us’ disease.” LaFavor lectured on HIV/AIDS education at numerous events in Minnesota, the Dakotas, and Kansas.

Dozens of St. Louisans also met the moment. Virgil Grandberry, for example, an employee of the St. Louis Public Health Department, identified a grave absence in highly de-facto segregated St. Louis, the need for an AIDS education and service organization of, by, and for Black St. Louisans. In 1989, he founded Blacks Assisting Blacks Against AIDS (BABAA). In 1991, he recruited Erise Williams to take the message to the Black male community at“Black nights” at Twist, Knights, and Magnolia’s, well know gay bars in the 1980s, and into the larger Black community. When Grandberry died (with AIDS) in 1992, Williams took full leadership of the expanding organization and remained at the helm until BABAA’s demise as in independent entity a decade later.

Many other St. Louis institutions and personalities dot the landscape of Katie Batza’s book: Washington University’s and Saint Louis University’s NIH-CDC HIV vaccine development centers; MCC-St. Louis; the legendary and much loved Sunshine Inn; Robert Rayford, the Black sixteen-year-old St. Louisan whose died of AIDS a decade before the first reported cases on the coasts; Michael Edland, an interior designer who helped start DOORWAYS in 1988; St. Louis Effort for AIDS (EFA) founder Daniel Flier; psychiatric nurse Bill LaRock and social worker Cathy Johnson, volunteers at EFA and the NAMES Project, who tried in 1990 to bring an ACT UP chapter to Louis, which proved to be a city not quite ready for it; and Trinity priest Bill Chapman. Several other LGBTQ-activist-familiar St. Louis names and places are referenced, quoted, and appear in footnotes and the research bibliography.

Another St. Louisan serves to conclude the work: Missouri state representative Ian Mackey whose heartfelt April 2022 floor speech rebuttal to an anti-LGBTQ right-wing Republican representative pushing one of dozens of anti-LGBTQ bills in the Missouri General Assembly became a viral moment: “I was afraid of people like you growing up…. [F]or eighteen years, I walked around with nice people like you who took me to ball games, who told me how smart I was, and who went to the ballot and voted for crap like this.” This impassioned speech provides the jumping off point for Batza to bring the reader to the present moment – MAGA, COVID-19, earth care, the 2024 election, multiple “don’t say gay” bills across the nation, Black Lives Matter, and the never-ending struggle against prejudice, intolerance, and bigotry, what Batza calls “the various tendrils of oppression and inequality.”

AIDS in the Heartland is an academic treatise written by an academic. It shines brightly and ever-so-humanly when it tells the “quieter history” of the heartland and its response to AIDS, revealing the stories and personalities of those who were there and now are quickly disappearing into history itself. It also gives the reader hope that, as Batza put it in the final paragraph of the book, “the heartland remains amorphous but infinitely flexible to include us all.”

Rodney Wilson was an HIV vaccine volunteer at the Saint Louis University AIDS Vaccine Evaluation Unit and a member of the AVEU’s Community Advisory Board from 1991 to 1996. He is the founder of LGBTQ+ History Month USA.