The first series of events organized in October 1994 for the inaugural LGBTQ+ History Month was a film festival on the campus of the University of Missouri-St. Louis, where I was completing a graduate degree in history. Ten films were screened on four successive Monday nights: October 3, 10, 17 and 24.

Among the selections were seven documentaries: Portrait of Jason (1967), Word is Out (1977), Before Stonewall (1984), Silent Pioneers (1985), Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt (1989), West Coast Crones (1991) and Framing Lesbian Fashion (1992).

Three feature films were also screened: Parting Glances (a 1986 gay male love story set in the early years of AIDS), The Killing of Sister George (a 1968 lesbian drama directed and produced by Baby Jane director-producer Robert Aldrich); and saved for closing-night special feature: The Boys in the Band (1970).

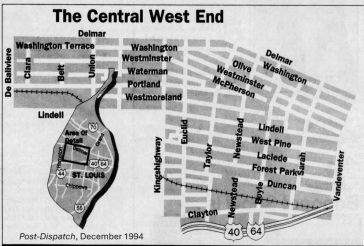

LGBTQ+ History Month debuted in St. Louis with a series of movie nights at UMSL (Courtesy image).

I had seen Boys for the first time in about 1991, more than twenty years after its theatrical release. I was 26 years old, ignorant of “gay history” and stunned to learn that a feature film released the year I was in kindergarten revolved around a community of gay men gathering to celebrate a birthday. That gay friendships even existed in the 1960s — and were written about in plays and projected on silver screens — was revelatory. I was a young man, newly out and having lived until age 23 in a small Missouri lead-mining town of 2,500 people on the rolling hills of the northern Ozarks, I was oblivious to a larger world full of all kinds of people. LGBTQ+ people in my hometown, if they existed (none was visible), did not gather in gay crowds and they did not throw gay birthday parties, but in New York City they did — and Mart Crowley captured that hopeful moment in gay space-and-time with an extraordinarily well executed play and equally powerful screenplay. Boys is rightly famous. Groundbreaking. Historic.

The Boys cast included nine actors. Seven of them were born during the worst years of the Great Depression. The other two were born just before the United States entered World War II. Most of the nine were gay men playing gay men. Five of these gay men succumbed to AIDS-related infections in the late-1980s and early-1990s. Only three cast members reached their 70s; two marked their 80th birthdays; and one will celebrate his 90th later this year. That man, the sole survivor of the original cast, played Hank the schoolteacher, the character with whom I most identified.

That actor, Laurence Luckinbill, has just completed a 10-year project — a hefty (at nearly 500 pages) memoir recounting his long, fascinating life. Affective Memories: How Chance and the Theater Saved My Life is an honest, outside-of-himself reflection full of personalities and pitfalls about an Arkansas boy from the Ozarks with a mountain of talent and two pocketfuls of dreams who had to duel the dragons of paternal alcoholism, paycheck-to-paycheck living and “nobodiness.” Affective Memories is about why that “nobody” from the sticks desperately wanted to be somebody from somewhere and how he pressed his way into the worlds of theater, television and film.

Luckinbill met Boys playwright Mart Crowley in the late 1950s when they were students at the American Catholic University in Washington, D.C. Crowley was from Mississippi; Luckinbill from Arkansas. They were born less than a year apart and both had alcoholic fathers. Their generational, geographical and familial affinities created an immediate sense of connection and cemented a life-long friendship. “My little brother” is how Luckinbill described Crowley after his passing in 2020.

A decade after their graduations from Catholic University, when Luckinbill was 33, their paths crossed again. Crowley asked Luckinbill to dine with him over a conversation about a new play, hot off the typewriter, ready to be staged for the world: “Cradled in his arm is a play script, held close to his breast as tenderly and tightly as a baby,” writes Luckinbill. Now we know that this dinner conversation was a moment of great import in LGBTQ+ history.

Asked by a doubtful Crowley if he would take a role, Luckinbill offered an immediate yes, making him the first actor to commit to a gay play written by a gay man about gay men in a country (before Stonewall, after all) that largely labeled those men as sick, sinful, and criminal. Even affiliating with this play and these people was a risk and Laurence Luckinbill did pay a price for identifying his face so closely with a gay character, losing a lucrative national advertising campaign for a new brand of cigarettes, True. “No fags smoke our fags,” was the message from corporate.

Luckinbill’s book is about an entire life and career, long before and long after Boys. Happily, however, he gives Boys the attention it deserves, devoting roughly 50 pages of his memoir to that magnificent three-year period in his life. He writes affectionately about the castmates (one of whom was recast before the play hit the stage); about the conflicts and hard work required to produce an unexpected success; about how the show made him momentarily question his own sexuality; and about how a one-week run of eight shows became a two-year run of 1,000 shows – and a film shot in ten weeks between May and July 1969.

Truly, gay playwright Mart Crowley made extraordinary, groundbreaking, and controversial gay history when he typed the first word of Boys on paper and again made history when he produced the stage show and shepherded the screenplay through production. The gay director of the play, Robert Moore, also made gay history. So did every gay castmate on that rooftop terrace stage. There’s lots of gay history in Boys. And some of it was made by straight man Laurence Luckinbill and with his engaging memoir about so many engrossing people and events we now have the great privilege of reading the last primary-source memories of Boys that we’ll ever have.