Long before speaking truth to power became standard operating procedure for those of us on the margins, St. Louisan Mabel Thorpe was doing it with panache.

Her first official scrape with the law was in 1913 during a strike by female telephone operators downtown. She was arrested for disobeying and insulting a police officer.

Then, the mid-1930s found her operating the Blackstone, a hotel at 4043 Olive. In its cocktail lounge, a loose (and queer-friendly) interpretation of liquor laws and the city’s “masquerade ordinance” quickly became the norm.

It was Thorpe’s violation of that ordinance—which forbid dressing “contrary to one’s gender” and remarkably remained on the books until the late 1980s—that raised the ire of neighbors and other concerned citizens.

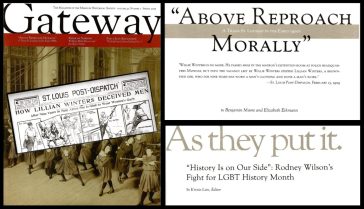

Photo courtesy of the St. Louis LGBT History Project.

But it was serving drinks after hours and not paying federal taxes that ultimately caught the attention of the city’s excise commissioner, Thomas Anderson, who revoked her license.

Rather than respond in the docile, orderly fashion of the day, Thorpe raised hell. She sued, claiming Anderson had gone after her license in an arbitrary manner. Ultimately, she lost.

She even served jail time, but only after taking a very public stand against business as usual during a trial at which she took the stand herself, as did several others who testified on her behalf.

Thorpe died in 1957, but she recently added yet another item to an already long list of achievements: she inspired Ian Darnell.

A candidate for a Ph.D. from the University of Illinois at Chicago, Darnell recently brought Thorpe and others to life in his lecture, Risky Refuges: Gay and Lesbian Bars in St. Louis, 1930s – 1960s.

The lecture, presented last month by the Missouri History Museum and the St. Louis LGBT History Project, covered history between the end of Prohibition in 1933 and the 1969 uprising at the Stonewall Inn, widely considered the opening salvo in the modern struggle for queer equality.

From the start, Darnell captured the attention of those in the lecture hall in the museum’s basement, which was packed to capacity in spite of the dreary and damp Wednesday evening underway outside.

Being able to search old newspapers electronically has changed the very face of historical research, Darnell began, adding triumphantly, if not a little geekily, that he considers the thought of more newspapers being digitized “very exciting.”

Laughter rippled throughout the audience, which was impressively diverse in terms of gender, orientation, and age.

Darnell, however, who is ready-made for the role of dashing young professor, was dead serious, and for the next hour and a half, he drew on visual images, facts and figures, and anecdotal narrative to conduct a tour of night spots where echoes of the last last call faded half a century or more before the birth of many attendees.

Along the way, Darnell drew connections between the city’s queer nightlife and other entities significant to the city’s culture, such as the business community, the police, neighborhoods, city planners, religious officials, politicians, and others.

Asked which of the characters he’d discovered he’d most like to meet, Darnell said having a drink with Mabel Thorpe at her cocktail lounge is at the top of his wish list.

“She lived this fabulous, glamorous life and was clearly a bit of an eccentric, which makes her an intriguing character,” he explained a few days after the lecture. “Also, she seems to have been so tough, and self-confident and persistent and brave.”

Darnell’s fascination with Thorpe, he explained, is based in part on the tension between what he knows about her and what remains hidden behind the veil of time.

“All of those newspaper clippings about her life, police reports describing officers’ interactions with her, court records—in one sense I have a good understanding of the details of her life and some sense of her character,” he said. “But other things are so mysterious, which fuels my interest.”

The roots of Darnell’s interest in local lore are at Saint Louis University where, as a Spanish and history major, he wrote his honors thesis on Communist organizing in the city during the Depression.

“That whet my appetite to do serious original research on St. Louis,” he said.

The summer of 2008 was pivotal for Darnell. He was living in his first apartment which, he would learn later, was right around the corner from Mabel Thorpe’s hotel. He’d just turned 21 and was going to gay bars in the Grove for the first time.

And he’d just read George Chauncy’s Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890 – 1940, which he calls an extraordinary book based on extensive, deep research.

From there, he found a more immediate, tactile source of inspiration—walking in St. Louis.

“The past is very obvious here,” Darnell said. “I guess it is in most places, but because St. Louis has declined so much, because there are so many abandoned buildings, so many hints of faded grandeur, the past is very present here, or seems to be. I couldn’t help but wonder if there was a version of the world described by George Chauncy here in St. Louis.”

Darnell found that very little had been written about queer history in St. Louis, but he soon learned that there were others who were asking the same questions, including Steven Brawley, whose blog has evolved into today’s St. Louis LGBT History Project.

Shortly thereafter, Darnell headed off to graduate school, where he dug into a serious and wide-ranging study of American history, which, he says, provides context for digging into St. Louis’ past.

“It’s intellectually exciting to me to uncover the history of where I’m from, where I know there are important stories that have gone untold,” he said.

Darnell said he sees the surge in interest in St. Louis history as part of a larger shift.

“I think the standard narrative of LGBT history that we often learn by cultural osmosis is that everything happens in New York or California,” he said. “People, I think, assume nothing important happens here, that people live boring lives, mostly in the closet. But a lot of people know that’s not true. And a lot of them are interested in hearing stories.”

On that score, Darnell delivered, and he plans to continue doing so.

To learn more, please visit the St. Louis LGBT History Project and Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis 1945 – 1992.

Patrick Collins is a writer who recently returned to St. Louis after living for many years in Portland, Oregon. You can reach him at [email protected].